Zine Alchemy, Part 1: a story about the healing power of making a zine

By Dal Kular

CW: references to racism, mental illness, transgenerational trauma.

Making zines with Dal Kular at a Peaks of Colour workshop 2024. Photo by Ai Narapol.

“No matter what happens, you can always make a zine. There’s no wrong way of making a zine. Zines can set you free.” Dr. Sheree Mack, zinester and poet.

Zines, those little self-made publications containing uncensored, radical and original content have been circulating underground for decades – hand to hand, via zine fests and distros, at gigs and via our letterboxes. From the margins of riot grrrl to Sweet Thang and especially during and since the pandemic, zines have infiltrated our everyday lives, democratising whose voices get to be heard. Zines are low-fi, diy and anarchic technology that is as simple as taking a single sheet of paper, a pen, maybe some sticky tape and crucially, an idea or an experiment to scribble, type, collage, handwrite across the page(s) and make something original and new. I love this definition of what a zine is or can be by Multitudes Zine Fest,

“A zine [pronounced like the ‘zine’ part of ‘magazine] is an independently created low-budget publication that can hold whatever you wish – poems, personal stories, political tracts, comics, artwork, recipes or rants. It might be a single author thing or holding the work of lots of contributors. It can be handwritten, typed, cut and paste with scissors and glue, or assembled on a computer. It’s like a mini magazine, a pamphlet, a love note. It might be a one-off thing, or a long-standing affair of many many issues. Either way, it’s usually only published as a short print run, often printed on a photocopier.”

In a hierarchical world being flooded with AI generated wor(l)ds and ideas, the ever increasing digital surveillance and censorship of our lives and data harvesting, and the corporate extraction of grassroot creative ideas which then become the next marketing buzz word, zines offer an analogue alternative to this by creating, practicing and sharing our knowledges between us in a way that is useless to capitalism and big data collection. This is otherwise creative production.

Image source: Dal Kular

Zines made by participatory researchers at University of Sheffield. Photo by Dal Kular

The unruly freedom of zines affords space for our individual and collective imaginings, healings, conjurings, creatings, philosophisings, rantings, ragings, engagings, playings, ponderings, possibilisings, root-makings, community-makings, connectings, thinkings, re-arrangings.

Pamphlets, flyers, posters and booklets containing seditious and revolutionary ideas distributed openly or secretly to garner support and solidarity have long been a part of meaningful change in many societies. Our beautiful world needs our wildest imagineering to conjure new possibilities for our collective future, at a time that feels like the end of time. Within zines we can proffer skills, wisdom, healing resources, stories, transmission of ancestral knowledges whereby they can become a compass and a guide to alternative ways of being, surviving and thriving outside of empire, outside of punitive systems and overcultures. These tiny tomes could become invaluable resources for our future generations. Zines are counter-narrative to mainstream publishing norms, systems and institutions. Here our voices become amplified. We unsilence and we disrupt. We inspire each other in the process of making, sharing and reading.

Zine-making can increase creative and personal confidence, improve mental wellbeing, foster courage and broaden horizons.

Although zine distribution may be small, the impact of a zine can be massive, having ripple effects both on the maker and the readers. Zine-making can increase creative and personal confidence, improve mental wellbeing, foster courage and broaden horizons. Readers of zines can learn about different lives and ways of being and living, get exposed to fresh ideas through the away-from-the-mainstream freedom of creative expression, find a sense of connection and camaraderie, hold a tactile artifact lovingly made, full of vibrations that can stir our subconscious minds. Zines are a joyous and profound technology that can benefit many of us.

Back in January 2020, just months before the covid pandemic locked us in our homes, I experienced the transformative potential of zine-making. I created a zine called ‘Wild Ink’ as part of my autoethnographic research for a masters in therapeutic writing exploring my identity, creativity and wildness using therapeutic zine-making methods. I wanted to understand the intersections of these in relation to my creative exile, and eventually, my creative return.

***

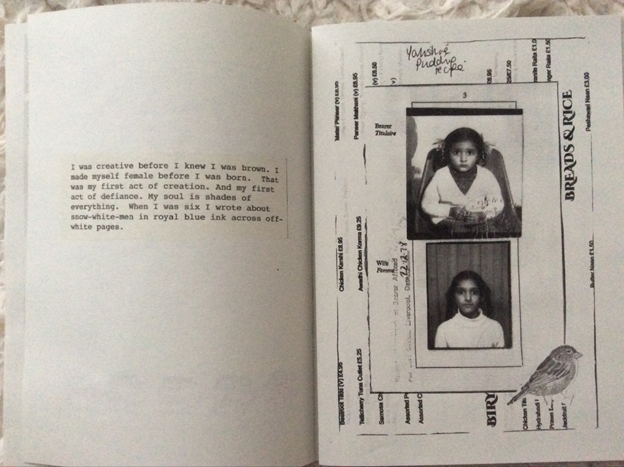

Image source: Dal Kular

Pages from Wild Ink zine by Dal Kular. The use of poetry alongside personal documents like my childhood passport helped me to intuitively create a narrative that gave me the ‘feels’ rather than making rational sense or needing literary merit. Using these images also helped me to access childhood dreams and potential.

As a creative and mischievous child of working class Punjabi Sikh immigrant parents, I knew I wanted to be a writer from the age of six. By the time I reached comprehensive school my writing dreams began eroding. Being placed in the worst class in the school, my pubescent hormones raged and my neurowildness began to emerge. The almost daily racism and the sheer boredom of lessons led me to becoming a school refuser. As a teenage fugitive I learnt the art of aimless roaming, hanging out in local parks and supermarket rooftops, writing poems and pretending to smoke herbal cigarettes. At 16 years old the school careers officer told me I could never be a writer and that I needed to get a proper job. I left school with 3 O-levels and signed on the dole.

I had no role models to look up to that looked like me who were from my background and who were creatives, even though I came from a profoundly creative cultural heritage.

This was the mid-eighties’s Up North, still reeling from Enoch Powell’s 1968 Rivers of Blood Speech and the miners strikes and all too frequent overt racism which sometimes meant physical attacks needing physical defence. I had no role models to look up to that looked like me who were from my background and who were creatives, even though I came from a profoundly creative cultural heritage. Crucially, I didn’t have that one person who told me, ‘you can do this’. As a kid I really needed that. These childhood experiences shaped the following decades of my life with that young writer haunting me all the way.

Image source: Dal Kular

Audre Lorde became an important part of my zine process and helped me to revisit my old school reports one of which alleged, ‘There are frankly, no prospects of O’level success’.

Making the Wild Ink zine became an experimental space to unravel aspects of my life and myself which had been hidden, smothered, colonised and suppressed for most of my adult life. It was my chance to re-historise. As an intuitively guided process, by the time I’d finished the zine it felt as if it had exploded into my life like a huge masala-mix firework, sending fragrant sparks far and wide, across timelines, histories, memories and landscapes. It felt healing, illuminating and cleansing.

Wild Ink helped me to realise that it had taken me over thirty years to find and heal my creative heart and creative inner child.

Wild Ink helped me to realise that it had taken me over thirty years to find and heal my creative heart and creative inner child. Poems in the zine revealed to me the cost of not following my creative impulses, especially on my mental health. It also helped me find my creative soul again and heal my ‘forever interrupted tongue’, a tongue interrupted by empire, partition and migration.

Image source: Dal Kular

My poem, Dear Aunty Audre from Wild Ink Zine. This poem was the first time I’d come face to face with the many ways in which I’d struggled with my mental health over the years. This poem was pivotal in helping me come to terms, recognise and accept my neurowildness as an integral part of my being, not an aberration from some colonised version of ‘normal’.

Dal Kular (she/her) is a writer, maker, zinester and facilitator of creative and nature-allied arts for healing, liberation and joy. She left school at 16 years old with 3 O-levels having been told she could never be a writer – returning to the power of words in her late forties – as an act of radical care and healing. Her debut poetry book (un)interrupted tongues, published by Fly on The Wall Press, emerged from a zine she created during her masters dissertation about the therapeutic and healing powers of zine-making. She loves making zines and handmade books. Dal’s latest zine is called ‘Dear Nature…’ and created during her writing residency with Peaks of Colour. She lives in Sheffield. You can read more of her work here.

Dal will be joining us for Synergi’s online series of events Building our own archives: Zines as a tool for resistance. Find out more here.